One of the noticeable geographical features of the Book of Mormon is the "neck of land."

People often ask me, "Where is the narrow neck of land?"

My answer: Ether 10:20. That's the only place in the scriptures where that phrase is used.

There is a "narrow neck" in Alma 63:5 and a "small neck of land" in Alma 22:32, but normally we treat different terms as meaning different things, and there's no reason not to follow that rule here.

IOW, the three terms might refer to the same geographical feature, but nothing in the text requires that. And if they refer to three different features, most models of Book of Mormon geography don't follow the text.

Relative terms. It's true that the passages also refer to the "land northward" and the "land southward," but these vague terms are relational, not proper nouns. If you live in Salt Lake, Provo is the land southward while Ogden is the land northward. If you live in Ogden, Salt Lake is the land southward and Brigham City is the land northward.

True, these vague terms might possibly be proper nouns--that's one of multiple working hypotheses--but nothing in the text requires them to be proper nouns, and if they are merely relative to where the speaker is, most models of Book of Mormon geography don't follow the text.

_____

What constitutes "small" or "narrow."

Lots of people have speculated about what these terms mean. Some authors who conflate the terms say the Isthmus of Tehuantepec is the small/narrow neck. Others think it's the Isthmus of Darien (Panama). Such features are only "narrow" or "small" when viewed on a map or from space.

I've looked at how the term was used in Joseph Smith's day. It turns out that these were common terms during the Revolutionary War. I have about 20 examples, all showing a diverse application including land bridges, peninsulas and islands, but all consistently featuring no more than about 15 miles in width, down to a few paces wide.

The point is, the references in the Book of Mormon are subject to lots of alternative interpretations; i.e., multiple working hypotheses.

_____

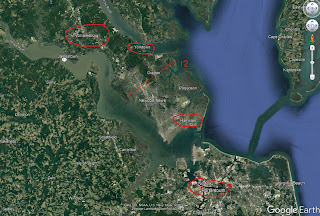

|

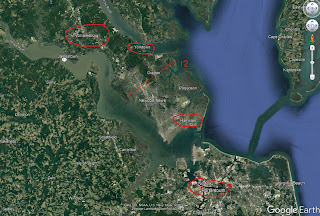

| Map of Virginia - Revolutionary War sites |

Here's what George Washington wrote:

I observe you are directed by the Governor to pay

particular attention to the fortifications in the State and that in consequence

of that you propose to garrison Portsmouth with 1200 men and to divide the

remainder of what troops you may have among the posts at York, Hampton &

Williamsburgh. The reasons you assign for having a garrison at Portsmouth are

good; but I can by no means think it would be prudent to have any considerable

stationary force at Hampton and York. These by being upon a narrow neck of land, would be in danger of

being cut off. The enemy might very easily throw up a few ships into York and

James’ river, as far as Queens Creek; and land a body of men there, who throw

up a few Redoubts, would intercept their retreat and oblige them to surrender

at discretion.

In this case, the "narrow neck of land" was about 12 miles wide at its widest point. And it's not an isthmus, either.

___

In this example, Washington wrote of a "narrow neck of land" that is about 7.5 miles across, from Sandwich, MA, to Buzzards Bay, MA.

Your Letter of the twelfth Instant I received Saturday Evening;1 I gave immediate attention to your Orders, and as it was judged extremely difficult, if not impracticable, to convey the Mortars by land, I gave Orders to the proper persons to prepare every thing necessary for conveying them by water, and to work day and night until they were compleated. This day they will go on board of Lighters to Sandwich from which place they are to be conveyed over the narrow neck of land to a place called Buzzards Bay,2 where they will be put on board two Lighters and conveyed to Rhode Island, from thence, keeping near the land, to New York.

_____

Washington referred to Manhattan as a narrow neck of land.

We discovered at the same time by their movements, and our Intelligence, that with the assistance of their Ships they intended to draw a Line round us, and cut of all communication, between the City and Country; thereby reducing us to the necessity of fighting our way out under every disadvantage—surrendering at discretion—or Starving—That they might have accomplished one or the other of these, if we had stayed at New York, is certain; because the City, as I presume you know, stands upon the point of a narrow Neck of Land laying between the East & North Rivers; & not more than a Mile Wide for Six or Seven Miles back; both Rivers having sufficient depth of Water for Ships of any burthen; and because they were not only Superior in Numbers, but could bring their whole force to any one point, whereas we, to keep open the communication were obliged to have an extended Line, or rather a chain of Posts, for near 18 Miles.

_____

The papers of Thomas Jefferson include a reference to Bunker's Hill on a "peninsula joined to the mainland by a neck of land" that was only "a few paces wide."

[13–18 Sep. 1786]

I am unable to say what was the number of Americans engaged in the affair of Bunker’s hill. I am able however to set right a gross falsehood of Andrews. He says that the Americans who were engaged were constantly relieved by fresh hands. This is entirely untrue. Bunker’s hill (or rather Brede’s hill whereon the action was) is a peninsula, joined to the main land by a neck of land almost level with the water, a few paces wide, and between one and two hundred toises long. On one side of this neck lay a vessel of war, and on the other several gun-boats. The body of our army was on the main land; and only a detachment had been sent into the peninsula. When the enemy determined to make the attack, they sent the vessel of war and gun-boats to take the position before mentioned to cut off all reinforcements, which they effectually did.

|

| the "small neck" at Bunker Hill |